It was another regular Thursday. I woke up to natural light pouring in from a window the size of the wall onto my bed. I was living in Brooklyn at the time, my full size bed swallowed the room, my closet was the size of a cupboard, and I had two roommates but I had my own bathroom and could afford my rent while living in New York so I counted those blessings over and over. It was time to leave and I entered the Rockaway Ave station to hop on the C train to High Street as I did each morning, debating whether it was worth it to transfer to the A at Utica — I decided against it and kept reading my book. Arriving at work in Dumbo, I entered the doors to campus and greeted my students and co-workers. Every Friday, each cohort did something called “Feelings Friday”, facilitated by the software engineering instructors, where students were invited to share anything from wins and mental blocks from the week to weekend plans and emotional struggles. It was a heavy space to help facilitate with zero mental health and counseling training so one of the teachers suggested we do a “Feelings Thursday” for the instructional staff and we all agreed by responding “yes” to the calendar invite.

Our bodies formed a circle and the sharing commences. Everyone talks about their upcoming plans, students they’re struggling with, and roommates they need to vent about. Suddenly it is my turn and the emotional dam I have meticulously built and tended to for almost a year completely breaks. I am a hurricane of tears, grief, and wailing. Transforming the entire atmosphere, I am having a complete mental breakdown. As I am sharing I watch my co-workers' faces take turns exhibiting empathy, mortification, and pure discomfort. I couldn’t tell you what I shared, but I definitely was not okay and now my biggest fear has come true: everyone knows. After the flood of tears and gushing rambling subsided there was an awkward silence heavy with terror. I imagine I reflexively made a joke so that the next co-worker could share without feeling obligated to produce a series of clumsy affirmations. Later my sweet, sweet manager attempted to console me by saying I “increased the vulnerability threshold for the entire team”, which she believed was a positive outcome. Regardless of the impact to the team, it was clear — I needed help.

This wasn’t a case of breaking after piled up microaggressions or having to push through consistent public challenges to my competence and qualifications. My entire team was incredibly supportive and generous with their time, commitment, and care — especially my manager. No. This was a case of being the only black woman, working in an industry where imposter syndrome is rampant and holding a job title where one is often encouraged to give more than they have the capacity to. I was a software engineering instructor being choked by crippling anxiety and imposter syndrome, spending everyday putting on everyone’s oxygen mask before my own. Eventually I ran out of air.

Back in 2018, there was nothing I wanted more than a career in tech. Baby girl simultaneously fell in love with coding and the internet around 2005, close to the height of MySpace. College graduation rolls around and after launching a couple failed businesses and juggling multiple freelance gigs, I was ready to make the transition into finally becoming the software engineer I dreamed of being back in middle school. I cried tears of joy and relief in my mom’s arms after being accepted into my desired coding bootcamp with a full scholarship. Before graduation, I was invited to join the instructional staff at a campus in Brooklyn, specifically created to increase access to a software engineering career for potential students making under $35,000 in annual income. Excited about the mission and what appeared to be alignment with my politics, I began interviewing for the role while still in the program. Passionate and curious about code, building projects, and serving marginalized communities — this seemed like a dream role. It turns out it was a dream I eventually felt overwhelmingly unequipped for.

Fast-forward to 2019, I had an emotional breakdown at work because I didn't have the tools to address my overwhelming imposter syndrome, provide the emotional labor and support my students needed as they navigated financial precarity while inside an exhausting educational program, and the strain on my mental health and capacity being a black woman in tech demands. After the public meltdown I joined the remote instructional team as fast as I could to retreat, recover, and lick my wounds. What’s the data on how long it takes black women to recover from workplace trauma and burnout? What’s the data on how much she spends in doctor’s appointments, on therapy, on wellness, and capacity recouping expenses? What’s the data on how much money she loses staying small, afraid of unraveling that completely again? What’s the data on the resource strain on her community who has to listen and watch her struggle, financially support her through crippling anxiety and depression, or rotate care shifts tending to completely avoidable work related crises?

Where’s the data that tells us what we already know? The first folks who feel the negative impacts of unethical software are the first to get pushed out of the industry creating the software. Make no mistake, this is by design. But as our social lives and planet are increasingly being shaped and sometimes dominated by technology, I dream of a reality where black feminist praxis is at the center of the collective imagination and development frameworks of software engineering teams. The solution cannot stop at “creating” more black women software engineers, it must extend to how we might transform the tech industry into one that centers their care and social genius. At Seeda School we have a 10 year vision to iterate on a solution to this massive problem by providing an ecosystem of support for black women at 3 stages in their career: skill development, job search, and career development. We’re currently in Phase 1 where our focus for the next 3 years is delivering intentional curriculum, content, and coaching to help you develop the skills to enter the tech industry as a software developer.

To be clear, I am deeply weary of the assumptions entangled in the word “solution” and believe all proposals are problematic in the hubris it requires, but if the tech industry is going to continue to exist, it cannot continue to exist like this. Where are all the black women in tech? They’re recovering from workplace trauma, they’re systematically being excluded, they’re self-selecting out of the industry citing lack of support and more. To the black woman looking to enter tech who needs more nuanced advice than “just have the confidence of a mediocre white man”, how might we transform the status quo? I would love to find out together.

Please register for this free workshop if you’re interested in becoming a web developer and have some ideas on what we must demand from an industry we must transform.

With gratitude,

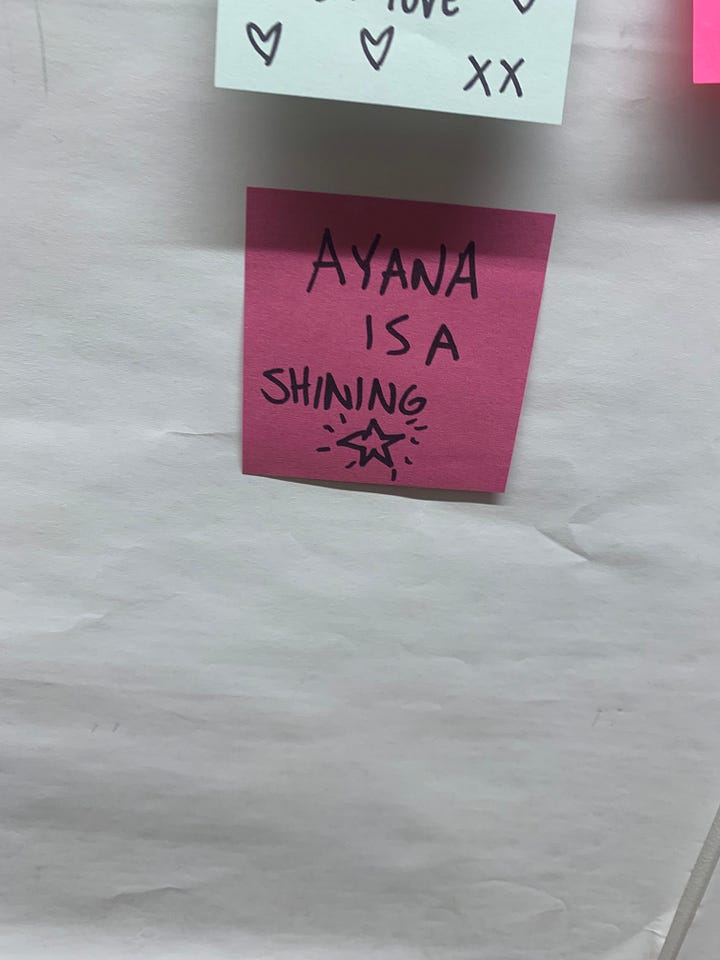

Ayana